The Kenyon College faculty voted to change from Kenyon units to semester hours. This change will go into effect for all students who start at the College in the fall of 2024. Both systems will be used throughout the course catalog with the Kenyon units being listed first.

The seminar in contemporary mathematics provides an introduction to the rich and diverse nature of mathematics. Topics covered vary from one semester to the next (depending on faculty expertise) but typically span algebra and number theory, dynamical systems, probability and statistics, discrete mathematics, topology, geometry, logic, analysis and applied math. The course includes guest lectures from professors at Kenyon, a panel discussion with upper-class math majors and opportunities to learn about summer experiences and careers in mathematics. The course goals are threefold: to provide an overview of modern mathematics, which, while not exhaustive, exposes students to some exciting open questions and research problems in mathematics; to introduce students to some of the mathematical research being done at Kenyon; and to expose students to useful resources and opportunities (at Kenyon and beyond) that are helpful in launching a meaningful college experience. This course does not count toward any requirement for the major. Prerequisite or corequisite: MATH 212 (or equivalent) and concurrent enrollment in another MATH, STAT or COMP course. Open only to first- or second-year students. Offered every fall semester.

Our intuitions about sets, numbers, shapes and logic all break down in the realm of the infinite. Seemingly paradoxical facts about infinity are the subject of this course. We discuss what infinity is, how it has been viewed through history, why some infinities are bigger than others and how a finite shape can have an infinite perimeter. This very likely is quite different from any mathematics course you have ever taken. This course focuses on ideas and reasoning rather than algebraic manipulation, though some algebraic work will be required to clarify big ideas. The class is a mixture of lecture and discussion, based on selected readings. Students can expect essay tests, frequent homework and writing assignments. This course does not count toward any major requirement. Students who have credit for MATH 222 may not receive credit for this course. No prerequisite. Offered occasionally.

The first course in the calculus sequence, this course covers the basic ideas of differential calculus. Differential calculus is concerned primarily with the fundamental problem of determining instantaneous rates of change. In this course, we study instantaneous rates of change from both a qualitative geometric and a quantitative analytic perspective. We cover in detail the underlying theory, techniques and applications of the derivative. Elementary differential equations and their applications are also introduced, along with the basics of anti-differentiation. Students who have 4 credit hours for calculus may not receive credit for MATH 111. This counts toward the core course requirement for the major. Prerequisite: solid grounding in algebra, trigonometry and elementary functions. Offered every semester.

This is the second course calculus sequence, this course focuses on integration, including Riemann sums, the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, techniques of integration, numerical methods, and applications of integration. This study leads into the analysis of differential equations by separation of variables, Euler's method, and slope fields. This counts toward the core course requirement for the major. Prerequisite: MATH 111 or the equivalent. Offered every semester.

This course examines an important and interesting part of the history of mathematics and, more generally, the intellectual history of humankind: the history of mathematics in the Islamic world. Some of the most fundamental notions in modern mathematics have their roots here, such as the modern number system, the fields of algebra and trigonometry, and the concept of algorithm, among others. In addition to studying specific contributions of medieval Muslim mathematicians in the areas of arithmetic, algebra, geometry and trigonometry in some detail, we examine the context in which Islamic science and mathematics arose, and the role of religion in this development. The rise of Islamic science and its interactions with other cultures (e.g., Greek, Indian and Renaissance European) tell us much about larger issues in the humanities. Thus, this course has both a substantial mathematical component (60-65 percent) and a significant history and social science component (35-40 percent), bringing together three disciplines: mathematics, history and religion. The course counts toward the Islamic Civilization and Cultures concentration but does not count toward any math major requirement. Prerequisite: solid knowledge of algebra and geometry.

This seven-week course focuses on the concept of convergence of infinite sequences and series of real numbers, with a focus on their applications to Calculus, culminating in an exploration of Taylor series representations of functions. Topics include evaluation of improper integrals, convergence and divergence of sequences, tests for convergence of series, polynomial approximations of functions, power series, and Taylor’s Theorem.

This course meets for the first seven weeks of the semester and counts toward the core course requirement for the major. Prerequisite: Math 112 or AP score of 5 on Calculus AB exam or an AB sub-score of 5 on the Calculus BC exam. Students with an AP score of 4 on the Calculus AB exam are encouraged to take the Calculus placement exam. Offered every semester.

This course examines differentiation and integration in three dimensions. Topics of study include functions of more than one variable, vectors and vector algebra, partial derivatives, optimization, and multiple integrals. Some of the following topics from vector calculus also are covered as time permits: vector fields, line integrals, flux integrals, curl and divergence. This counts toward the core course requirement for the major. Prerequisite: MATH 112 or a score of 5 on the AB calculus AP exam, or an AB sub-score of 5 on the BC calculus AP exam. Offered every semester.

This course introduces students to mathematical reasoning and rigor in the context of set-theoretic questions. The course covers basic logic and set theory, relations — including orderings, functions and equivalence relations — and the fundamental aspects of cardinality. The course emphasizes helping students read, write and understand mathematical reasoning. Students are actively engaged in creative work in mathematics. Students interested in majoring in mathematics should take this course no later than the spring semester of their sophomore year. Advanced first-year students interested in mathematics are encouraged to consider taking this course in their first year. This counts toward the core course requirement for the major. This course cannot be taken pass/D/fail. Prerequisite: MATH 213. Offered every semester.

This course focuses on the study of vector spaces and linear functions between vector spaces. Ideas from linear algebra are useful in many areas of higher-level mathematics. Moreover, linear algebra has many applications to both the natural and social sciences, with examples arising in fields such as computer science, physics, chemistry, biology and economics. In this course, we use a computer software system, such as Maple or Matlab, to investigate important concepts and applications. Topics to be covered include methods for solving linear systems of equations, subspaces, matrices, eigenvalues and eigenvectors, linear transformations, orthogonality and diagonalization. Applications are included throughout the course. This counts toward the core course requirement for the major. Prerequisite: MATH 213. Generally offered three out of four semesters.

Combinatorics is, broadly speaking, the study of finite sets and finite mathematical structures. A great many mathematical topics are included in this description, including graph theory; combinatorial designs; partially ordered sets; networks; lattices and Boolean algebras; and combinatorial methods of counting, including combinations and permutations, partitions, generating functions, recurring relations, the principle of inclusion and exclusion, and the Stirling and Catalan numbers. This course covers a selection of these topics. Combinatorial mathematics has applications in a wide variety of nonmathematical areas, including computer science (both in algorithms and in hardware design), chemistry, sociology, government and urban planning; this course may be especially appropriate for students interested in the mathematics related to one of these fields. This counts toward the discrete/combinatorial (column C) elective requirement for the major. Prerequisite: MATH 212 or a score or 5 on the BC calculus AP exam. Offered every other year.

The "Elements" of Euclid, written over 2,000 years ago, is a stunning achievement. The "Elements" and the non-Euclidean geometries discovered by Bolyai and Lobachevsky in the 19th century form the basis of modern geometry. From this start, our view of what constitutes geometry has grown considerably. This is due in part to many new theorems that have been proved in Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometry but also to the many ways in which geometry and other branches of mathematics have come to influence one another over time. Geometric ideas have widespread use in analysis, linear algebra, differential equations, topology, graph theory and computer science, to name just a few areas. These fields, in turn, affect the way that geometers think about their subject. Students consider Euclidean geometry from an advanced standpoint but also have the opportunity to learn about non-Euclidean geometries. This counts toward the continuous/analytic (column B) elective requirement for the major. Prerequisite: MATH 222. Offered every other year.

Looking at a problem in a creative way and seeking out different methods toward solving it are essential skills in mathematics and elsewhere. In this course, students build their problem-solving intuition and skills by working on challenging and fun mathematical problems. Common problem-solving techniques in mathematics are covered in each class meeting, followed by collaboration and group discussions, which are the central part of the course. When offered in the fall semester, the course culminates with the Putnam exam on the first Saturday in December. Interested students who have a conflict with that date should contact the instructor. This does not count toward any requirement for the major. Prerequisite: MATH 212 or a score of 5 on the BC calculus exam.

This course is an introduction to ordinary differential equations (ODEs). The course discusses techniques for finding, analyzing, and interpreting solutions of ODEs using exact methods, numerical methods, series solutions and qualitative approaches. We discuss first-and second-order differential equations, as well as first-order systems of differential equations. Applications are woven throughout the course. Other topics, as time permits. This course counts toward the computational/modeling (column D) elective requirement for the major. Prerequisite: MATH 224.

In biological sciences, mathematical models are becoming increasingly important as tools for turning biological assumptions into quantitative predictions. In this course, students learn how to fashion and use these tools to explore questions ranging across the biological sciences. We survey a variety of dynamic modeling techniques, including both discrete and continuous approaches. Biological applications may include population dynamics, molecular evolution, ecosystem stability, epidemic spread, nerve impulses, sex allocation and cellular transport processes. The course is appropriate both for math majors interested in biological applications and for biology majors who want the mathematical tools necessary to address complex, contemporary questions. As science is becoming an increasingly collaborative effort, biology and math majors are encouraged to work together on many aspects of the course. Coursework includes homework, problem-solving exercises and short computational projects. Final independent projects require the development and extension of an existing biological model selected from the primary literature. This course builds on (but is not limited by) an introductory-level knowledge base in both math and biology. Interested biology and math majors lacking a prerequisite are encouraged to consult with the instructor. This counts toward the computational/modeling/applied (column D) elective requirement for the major. Prerequisite: STAT 106 or MATH 111 or 112 (or any math or statistics AP credit of 4 or 5), and either BIOL 115 or 116. Offered every other year.

This course is a mathematical examination of the formal language most common in mathematics: predicate calculus. We examine various definitions of meaning and proof for this language and consider its strengths and inadequacies. We develop some elementary computability theory en route to rigorous proofs of Godel's Incompleteness Theorems. Concepts from modal logic, model theory and other advanced topics are discussed as time permits. This counts toward the algebraic (column A) elective for the major. Prerequisite: MATH 222. Offered occasionally.

This is a second course focusing on the use of linear algebra to solve large-scale data and image problems. Applications may include, but are not limited to, tomography to reconstruct a 3-D image of a brain, regression to model climate data, prediction of long-term behavior of populations, fractal generation, image-blurring and edge detection, algorithmic approaches to suggest movies to users, linear classifiers to identify cancer risk, and linear optimization for resource allocation. Linear algebra concepts and tools are developed as needed to address the presented problems. In addition to extensions of topics from the first linear algebra course, this course includes a selection of topics from the following list: abstract vector spaces, orthogonal subspaces and projection operators, norms and inner products, Markov matrices, matrix decompositions (LU, Cholesky, Schur, SVD), and support vector machines. Solutions to or simulations of the applied problems presented are implemented in Matlab or similar software. This course counts toward the applied focus (column D) elective for the major. Prerequisite: Math 224.

Patterns within the set of natural numbers have enticed mathematicians for well over two millennia, making number theory one of the oldest branches of mathematics. Rich with problems that are easy to state but fiendishly difficult to solve, the subject continues to fascinate professionals and amateurs alike. In this course, we get a glimpse at both the old and the new. In the first two-thirds of the semester, we study topics from classical number theory, focusing primarily on divisibility, congruences, arithmetic functions, sums of squares and the distribution of primes. In the final weeks, we explore some of the current questions and applications of number theory. We study the famous RSA cryptosystem, and students read and present some current (carefully chosen) research papers. This counts toward either a discrete/combinatorial (column C) or an algebraic (column A) elective requirement for the major. Prerequisite: MATH 222, prerequisite or corequisite: MATH 212. Offered every other year.

Coding theory (the theory of error-correcting codes), and cryptography are two important applications of algebra and discrete mathematics to information and communications systems. While coding theory is concerned with the reliability of communication, the main problem of cryptography is the security and privacy of communication. Applications of coding theory range from enabling the clear transmission of pictures from distant planets to quality of sound in compact disks and wireless communication. Error correcting codes play a key role in quantum computing. With the ever increasing role of digital communication, online transactions, the general dependence on electronic systems in modern life, and the emergence of quantum computers, the importance of these fields grows each day. In this course, students will learn the basic ideas of coding theory and cryptography, understand their mathematical foundations, and learn how mathematical tools can be used to devise useful error correcting codes and cryptographic systems. A selection of topics from these two disciplines will be discussed including basics of block coding, linear codes, Hamming codes, cyclic codes, symmetric-key and public-key cryptography, digital signatures, and code-based cryptography. Other than some basic linear algebra, the necessary mathematical background (mostly abstract algebra) is covered within the course. This counts toward either a discrete/combinatorial (column C) or an algebraic (column A) elective requirement for the major. Prerequisite: MATH 222 and MATH 224. Offered every other year.

This course provides a survey of several techniques used in applied mathematics. We discuss the mathematical formulation of models for a variety of processes that arise in the natural and social sciences. We derive the appropriate equations to describe these processes and use techniques from calculus, differential equations, linear algebra and numerical methods when needed. This course may touch on topics like dimensional analysis, scaling, kinetic equations and perturbation methods. Students have the opportunity to investigate applications within their fields of interest such as biology, medicine, physics, chemistry and finance. A strong background in calculus is essential; a familiarity with differential equations is recommended but not required. This counts toward the computation/modeling/applied (column D) elective requirement for the major. Prerequisite: MATH 213. Sophomore standing. Offered every other year.

Ordinary differential equations (ODEs) arise naturally to model systems that occur in physics, biology, chemistry and economics. This course discusses techniques for finding, analyzing, and interpreting solutions of ODEs using analytic, numerical and qualitative techniques. We discuss first-and second-order ODEs, as well as first-order systems of ODEs. Applications are woven throughout the course. Other topics, as time permits. This course counts toward the computational/modeling (column D) elective requirement for the major. Prerequisite: MATH 224. Offered every other fall.

Abstract algebra is the study of algebraic structures that describe common properties and patterns exhibited by seemingly disparate mathematical objects. The phrase "abstract algebra" refers to the fact that some of these structures are generalizations of the material from high school algebra relating to algebraic equations and their methods of solution. In this course, we focus entirely on group theory. A group is an algebraic structure that allows one to describe symmetry in a rigorous way. The theory has many applications in physics and chemistry. Since mathematical objects exhibit pattern and symmetry as well, group theory is an essential tool for the mathematician. Furthermore, group theory is the starting point in defining many other more elaborate algebraic structures including rings, fields and vector spaces. We cover the basics of groups, including the classification of finitely generated abelian groups, factor groups, the three isomorphism theorems and group actions. The course culminates in a study of Sylow theory. Throughout the semester there is an emphasis on examples, many of them coming from calculus, linear algebra, discrete math and elementary number theory. There also are a couple of projects illustrating how a formal algebraic structure can empower one to tackle seemingly difficult questions about concrete objects (e.g., the Rubik's cube or the card game SET). Finally, there is a heavy emphasis on the reading and writing of mathematical proofs. Junior standing is recommended. This counts toward the algebraic (column A) elective requirement for the major. Prerequisite: MATH 222. Offered every other fall.

This course provides a calculus-based introduction to probability. Topics include basic probability theory, random variables, discrete and continuous distributions, mathematical expectation, functions of random variables and asymptotic theory. This counts toward either a discrete/combinatorial (column C) or continuous/analytic (column B) elective requirement for the major. Prerequisite: MATH 213. Offered every fall.

This course is a first introduction to real analysis. "Real" refers to the real numbers. Much of our work revolves around the real number system. We start by carefully considering the axioms that describe it. "Analysis" is the branch of mathematics that deals with limiting processes. Thus the concept of distance is also a major theme of the course. In the context of a general metric space (a space in which we can measure distances), we consider open and closed sets, limits of sequences, limits of functions, continuity, completeness, compactness and connectedness. Other topics may be included if time permits. Junior standing is recommended. This counts toward the continuous/analytic (column B) elective requirement for the major. Prerequisite: MATH 212 and 222. Offered every other fall.

This course introduces students to the concepts, techniques and power of mathematical modeling. Both deterministic and probabilistic models are explored, with examples taken from the social, physical and life sciences. Students engage cooperatively and individually in the formulation of mathematical models and in learning mathematical techniques used to investigate those models. This counts toward the computational/modeling/applied (column D) elective requirement for the major. Prerequisite: STAT 106 and MATH 224 or 258. Offered every other year.

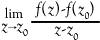

The course starts with an introduction to the complex numbers and the complex plane. Next, students are asked to consider what it might mean to say that a complex function is differentiable (or analytic, as it is called in this context). For a complex function that takes a complex number z to f(z), it is easy to write down (and make sense of) the statement that f is analytic at z if

exists. Subsequently, we study the amazing results that come from making such a seemingly innocent assumption. Differentiability for functions of one complex variable turns out to be very different from differentiability in functions of one real variable. Topics covered include analyticity and the Cauchy-Riemann equations, complex integration, Cauchy's Theorem and its consequences, connections to power series, and the Residue Theorem and its applications. This counts toward the continuous/analytic (column B) elective requirement for the major. Prerequisite: MATH 212 and MATH 224. Offered every other year.

Topology is an area of mathematics concerned with properties of geometric objects that remain the same when the objects are "continuously deformed." Three of these key properties in topology are compactness, connectedness and continuity; the mathematics associated with these concepts is the focus of the course. Compactness is a general idea helping us to more fully understand the concept of limit, whether of numbers, functions or even geometric objects. For example, the fact that a closed interval (or square, or cube, or n-dimensional ball) is compact is required for basic theorems of calculus. Connectedness is a concept generalizing the intuitive idea that an object is in one piece: The most famous of all the fractals, the Mandelbrot Set, is connected, even though its best computer-graphics representation might make this seem doubtful. Continuous functions are studied in calculus, and the general concept can be thought of as a way by which functions permit us to compare properties of different spaces or as a way of modifying one space so that it has the shape or properties of another. Engineering, chemistry and physics are among the subjects that find topology useful. The course touches on selected topics that are used in applications. This counts toward the continuous/analytic (column B) elective requirement for the major. Prerequisite: MATH 222 or permission of instructor. Generally offered every two to three years.

Partial differential equations (PDEs) arise naturally to model spatially-dependent systems that occur in physics, biology, and finance. This course covers analytic, numerical and qualitative methods for the solution and understanding of PDEs. Topics may include separation of variables, transform methods, nonlinear waves and shocks, and computational methods. This counts toward the computation/modeling/applied (column D) elective requirement for the mathematics major. Prerequisite: MATH 333. Offered every other spring.

This course picks up where MATH 335 ends, focusing primarily on rings and fields. Serving as a good generalization of the structure and properties exhibited by the integers, a ring is an algebraic structure consisting of a set together with two operations — addition and multiplication. If a ring has the additional property that division is well-defined, one gets a field. Fields provide a useful generalization of many familiar number systems: the rational numbers, the real numbers and the complex numbers. Topics to be covered include polynomial rings; ideals; homomorphisms and ring quotients; Euclidean domains, principal ideal domains and unique factorization domains; the Gaussian integers; factorization techniques; and irreducibility criteria. The final block of the semester serves as an introduction to field theory, covering algebraic field extensions, symbolic adjunction of roots, construction with ruler and compass, and finite fields. Throughout the semester there is an emphasis on examples, many of them coming from calculus, linear algebra, discrete math and elementary number theory. There also is a heavy emphasis on the reading and writing of mathematical proofs. This counts toward the algebraic (column A) elective requirement for the major. Prerequisite: MATH 335. Offered every other spring.

This course follows MATH 341. Topics include a study differentiation and (Riemann) integration of functions of one variable, sequences and series of functions, power series and their properties, iteration and fixed points. Other topics may be included as time permits. For example: a discussion of Newton's method or other numerical techniques; differentiation and integration of functions of several variables; spaces of continuous functions; the implicit function theorem; and everywhere continuous, nowhere differentiable functions. This counts toward the continuous/analytic (column B) elective requirement for the major. Prerequisite: MATH 341. Offered every other spring.

The senior seminar in mathematics provides a structure to aid students in successfully completing the Mathematics and Statistics Capstone requirement. Students who participate in a 3-2 program ordinarily take this course in their junior year. Students with December anticipated graduation dates take the seminar in their sixth semester (in the third semester before graduation). This schedule makes it possible for students who do not succeed in their first try at the capstone to take full advantage of the “second chance” option without delaying their graduation timeline.

Students who do not successfully complete their capstone in the fall semester will be assigned NG (no grade) at the end of the senior seminar. This designation will change to a CR when the student successfully completes the capstone, usually at the end of the following semester. This course is a core requirement for the mathematics major. Prerequisite: MATH 222 and at least one 300+-level course in Mathematics or Statistics. The course is offered every fall semester. The course is credit/no credit.

Individual study is a privilege reserved for students who want to pursue a course of reading or complete a research project on a topic not regularly offered in the curriculum. It is intended to supplement, not take the place of, coursework. Individual study cannot be used to fulfill requirements for the major. To qualify, a student must identify a member of the mathematics department willing to direct the project. The professor, in consultation with the student, creates a tentative syllabus (including a list of readings and/or problems, goals and tasks) and describes in some detail the methods of assessment (e.g., problem sets to be submitted for evaluation biweekly; a 20-page research paper submitted at the course's end, with rough drafts due at given intervals; and so on). The department expects the student to meet regularly with his or her instructor for at least one hour per week. All standard enrollment/registration deadlines for regular college courses apply. Because students must enroll for individual studies by the end of the seventh class day of each semester, they should begin discussion of the proposed individual study by the semester before, so that there is time to devise the proposal and seek departmental approval. Individual study courses may be counted as electives in the mathematics major, subject to consultation with and approval by the Department of Mathematics and Statistics. Permission of instructor and department chair required. No prerequisite.

This course consists largely of an independent project in which students read several sources to learn about a mathematical topic that complements material studied in other courses, usually an already completed depth sequence. This study culminates in an expository paper and a public or semi-public presentation before an audience consisting of at least several members of the mathematics faculty as well as an outside examiner. Permission of department chair required. Prerequisite: senior standing and the completion of at least one two-semester sequence at the junior-senior level.