My first day interning at the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) had its own soundtrack. It was the murmured awe of patrons flooding the security check as they stepped into the museum. It was the smooth contact of stroller wheels on the tiled floor and the whispered conversations echoing through the lobby. I was wearing my best business casual and feigning composure.

I had been dreaming of this day since visiting D.C. this past October. After obsessing over my application, it was so satisfying and also incredibly nerve-wracking to finally start my adventure. Museums are one of the places where far-off, sometimes forgotten history comes to life. What an incredible honor to be working at a place where history is not just theoretical, but the bread and butter of all who wander the building. What a unique opportunity to apply my education to the transformative world of museums.

On that first day, I met the other interns and some of the museum’s staff members. Each intern is assigned to different departments in the museum: education, member relations, and cataloguing, to name a few. My department is housed in the Office of Curatorial Affairs and I work with the publications and digitization team to bring our collections to life online and in print.

The publications side of things seemed familiar enough. I write here and in other places online; I know how to scour a document for a misplaced comma. In my position, I proofread drafts of articles that go online as Collection Stories, which explore objects in our collection with respect to their history and importance. I assist curators with research on specific topics and work closely with the editorial staff in the production of the Double Exposure photography book series.

It was the digitization part of the job that swept me off my feet. I have no formal experience with digitization. I know how to scan a document so I can send a PDF to a friend, and I certainly know how to take a picture on my phone. But at NMAAHC, the technology is a bit more complicated. Anything from photographs to dresses to tins of hair product (Madame C.J. Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower, to be exact) are imaged by high-powered cameras (at our photo station, above) and then processed as digital images. Then, they can be used in our online collection search feature or other places online. With the help of my wonderful colleagues on NMAAHC’s DigiTeam, I took a crash course on photography. It is more than simply pointing and shooting. We create the highest quality image possible, paying attention to color accuracy, resolution, and closely refined focus and lighting.

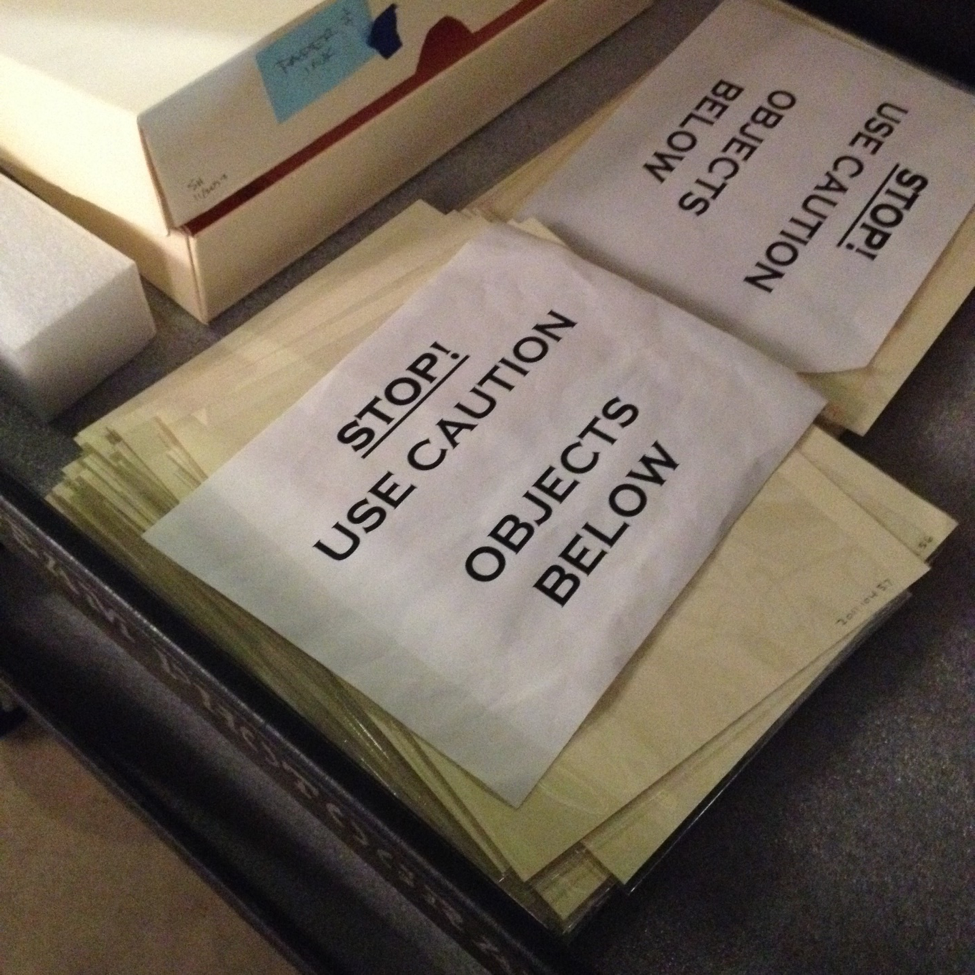

We keep our collections safe while we’re imaging them with these instructive signs!

I never thought I’d be discussing the finer points of color theory and the color space (a way to semi-mathematically plot colors on a 3-D grid) as part of my internship. The technical aspects of digitization were certainly challenging, so when I was faced with imaging my first objects, I didn’t anticipate the joy and wonder I’d feel.

My first digitization project was imaging some lesser-known photographs taken by James Van Der Zee, legendary photographer of the Harlem Renaissance. They included a cyanotype (a special photograph printed in shades of blue), a silver gelatin print, and a hand painted tintype (this was especially delicate because the image was physically imprinted on a thin sheet of tin). The cyanotype was the most stunning to me. It showed a stylish African American man holding a book with a fancy flower pinned to his lapel. Something about his calm and studied gaze was inherently beautiful. Since these images were all captured in the 1920s, they represented a time and place I had read much about, but had no real contact with.

My first exposure to Van Der Zee was at Kenyon, in a first-year English course with Jené Schoenfeld. We were reading Harlem Renaissance writers, and Van Der Zee, as a leading figure of the period and a talented photographer, served as a bit of historical framing for our class discussions. Holding one of his original photographs, almost a century old, seemed otherworldly. This was a priceless piece of history, connecting me to a time when African Americans in New York blossomed with creativity and life to create the Harlem Renaissance. One day, the photographs will be all online for the public to peruse them and learn more about Van Der Zee and his work.

I am in awe at the experience of working closely with history and touching the past in such a profound way. This experience, though only a small segment of what my internship entailed, reminds me of how securely history is entwined with our lives. We only have the opportunity to touch history every now and then, but we have the opportunity to make it every day.